By Michael Arsenault, Director of Product Marketing for AEC DSPs, Marvell

Rack connectivity is undergoing a historic transformation. Data center operators are demanding both scale-up and scale-out connectivity that can move more data across longer distances and between more systems, while delivering unprecedented levels of energy efficiency and reliability.

To help cable providers and their customers meet these challenges, Marvell has launched the Golden Cable initiative, designed to accelerate the development of active electrical cables (AECs). AECs are a rapidly growing class of high-bandwidth, enhanced copper interconnects used to link servers, switches, NICs and other assets in the same rack or across adjacent racks (about two to nine meters).

The Golden Cable initiative delivers a validated cable architecture tested across leading platforms and built on industry-leading software, reference designs, technical data, firmware and comprehensive support. Participants can combine these assets with their own technology to develop unique AECs powered by DSPs, optimized for specific customer requirements and use cases.

To further enhance performance and ensure broad compatibility, Golden Cable AECs are rigorously tested in the Marvell Cloud Interoperability Lab. Here, cables are validated across a wide range of customized configuration scenarios involving leading XPUs, CPUs, NICs, servers, switches, optical modules and other critical infrastructure components. This process enables Marvell and its partners to validate AEC firmware before cables reach end-customers, significantly accelerating customer qualification and deployment timelines. The result is greater confidence from the first plug-in.

The Golden Cable initiative is designed to rapidly scale and empower the cable partner ecosystem, enabling Marvell to meet accelerating market demand at true hyperscale speed. By operating in close alignment with key partners, Marvell is achieving many of the benefits of near‑vertical integration, while maintaining the flexibility and scalability of a partner‑driven model.

By Khurram Malik, Senior Director of Marketing, Custom Cloud Solutions, Marvell

Can AI beat a human at the game of twenty questions? Yes.

And can a server enhanced by CXL beat an AI server without it? Yes, and by a wide margin.

While CXL technology was originally developed for general-purpose cloud servers, the technology is now finding a home in AI as a vehicle for economically and efficiently boosting the performance of AI infrastructure. To this end, Marvell has been conducting benchmark tests on different AI use cases.

In December, Marvell, Samsung and Liqid showed how Marvell® StructeraTM A CXL compute accelerators can reduce the time required for conducting vector searches (for analyzing unstructured data within documents) by more than 5x.

In February, Marvell showed how a trio of Structera A CXL compute accelerators can process more queries per second than a cutting-edge server CPU and at a lower latency while leaving the host CPU open for different computing tasks.

Today, this blog post will show how Structera CXL memory expanders can boost performance of inference tasks.

AI and Memory Expansion

Unlike CXL compute accelerators, CXL memory expanders do not contain additional processing cores for near-memory computing. Instead, they supersize memory capacity and bandwidth. Marvell Structera X, released last year, provides a path for adding up to 4TB of DDR5 DRAM or 6TB of DDR4 DRAM to servers (12TB with integrated LZ4 compression) along with 200GB/second of additional bandwidth. Multiple Structera X modules, moreover, can be added to a single server; CXL modules slot into PCIe ports rather than the more limited DIMM slots used for memory.

By Khurram Malik, Senior Director of Marketing, Custom Cloud Solutions, Marvell

While CXL technology was originally developed for general-purpose cloud servers, it is now emerging as a key enabler for boosting the performance and ROI of AI infrastructure.

The logic is straightforward. Training and inference require rapid access to massive amounts of data. However, the memory channels on today’s XPUs and CPUs struggle to keep pace, creating the so-called “memory wall” that slows processing. CXL breaks this bottleneck by leveraging available PCIe ports to deliver additional memory bandwidth, expand memory capacity and, in some cases, integrate near-memory processors. As an added advantage, CXL provides these benefits at a lower cost and lower power profile than the usual way of adding more processors.

To showcase these benefits, Marvell conducted benchmark tests across multiple use cases to demonstrate how CXL technology can elevate AI performance.

In December, Marvell and its partners showed how Marvell® StructeraTM A CXL compute accelerators can reduce the time required for vector searches used to analyze unstructured data within documents by more than 5x.

Here’s another one: CXL is deployed to lower latency.

Lower Latency? Through CXL?

At first glance, lower latency and CXL might seem contradictory. Memory connected through a CXL device sits farther from the processor than memory connected via local memory channels. With standard CXL devices, this typically results in higher latency between CXL memory and the primary processor.

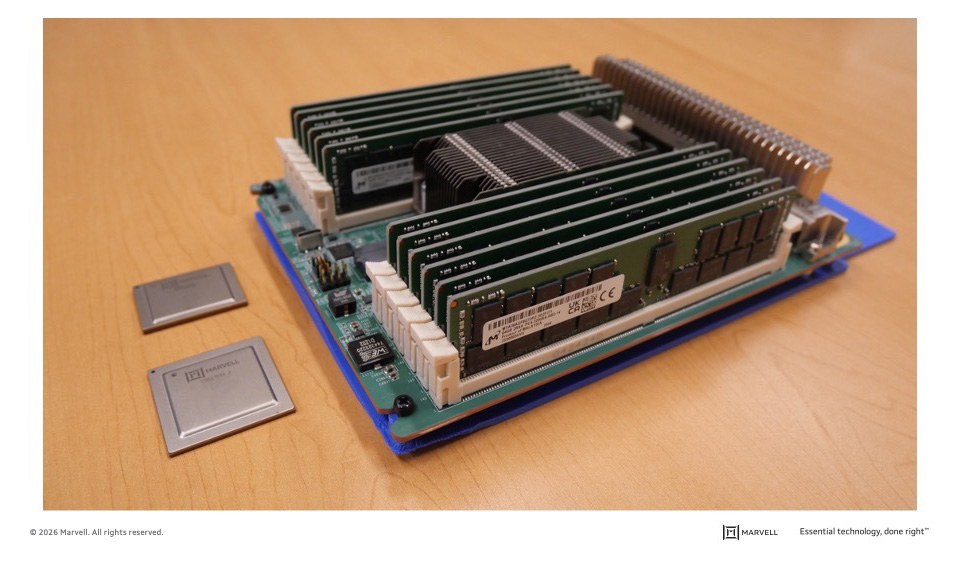

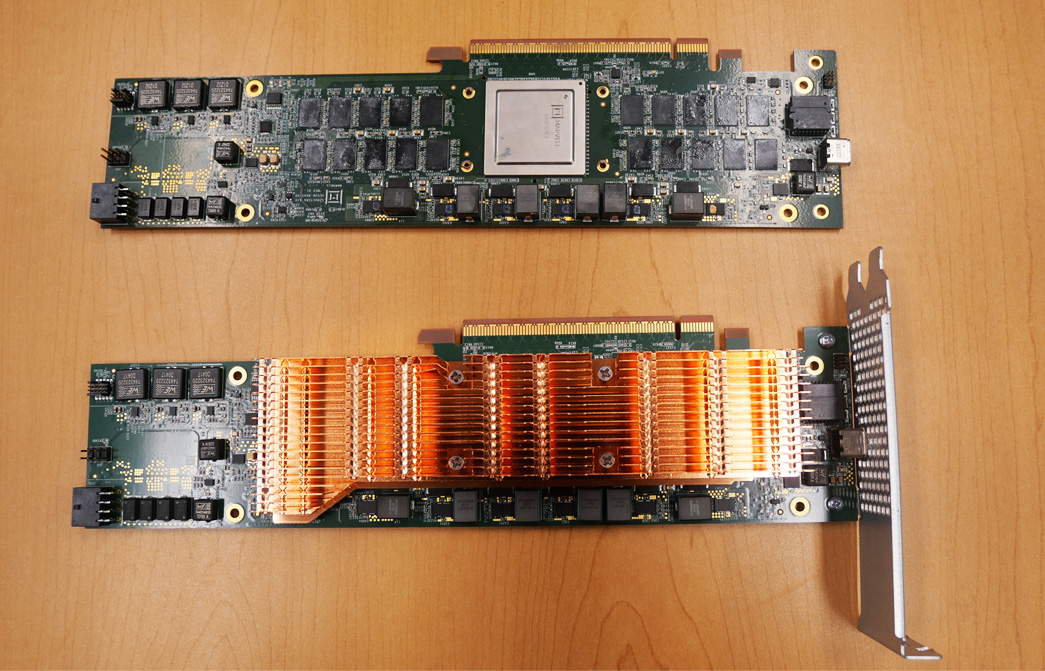

Marvell Structera A CXL memory accelerator boards with and without heat sinks.

By Rohan Gandhi, Director of Product Management for Switching Products, Marvell

Power and space are two of the most critical resources in building AI infrastructure. That’s why Marvell is working with cabling partners and other industry experts to build a framework that enables data center operators to integrate co-packaged copper (CPC) interconnects into scale-up networks.

Unlike traditional printed circuit board (PCB) traces, CPCs aren’t embedded in circuit boards. Instead, CPCs consist of discrete ribbons or bundles of twinax cable that run alongside the board. By taking the connection out of the board, CPCs extend the reach of copper connections without the need for additional components such as equalizers or amplifiers as well as reduce interference, improve signal integrity, and lower the power budget of AI networks.

Being completely passive, CPCs can’t match the reach of active electrical cables (AECs) or optical transceivers. They extend farther than traditional direct attach copper (DAC) cables, making them an optimal solution for XPU-to-XPU connections within a tray or connecting XPUs in a tray to the backplane. Typical 800G CPC connections between processors within the same tray span a few hundred millimeters while XPU-to-backplane connections can reach 1.5 meters. Looking ahead,1.6T CPCs based around 200G lanes are expected within the next two years, followed by 3.2T solutions.

While the vision can be straightforward to describe, it involves painstaking engineering and cooperation across different ecosystems. Marvell has been cultivating partnerships to ensure a smooth transition to CPCs as well as create an environment where the technology can evolve and scale rapidly.

By Nicola Bramante, Senior Principal Engineer, Connectivity Marketing, Marvell

The exponential growth in AI workloads drives new requirements for connectivity in terms of data rate, associated bandwidth and distance, especially for scale-up applications. With direct attach copper (DAC) cables reaching their limits in terms of bandwidth and distance, a new class of cables, active copper cables (ACCs), are coming to market for short-reach links within a data center rack and between racks. Designed for connections up to 2 to 2.5 meters long, ACCs can transmit signals further than traditional passive DAC cables in the 200G/lane fabrics hyperscalers will soon deploy in their rack infrastructures.

At the same time, a 1.6T ACC consumes a relatively miniscule 2.5 watts of power and can be built around fewer and less sophisticated components than longer active electrical cables (AECs) or active optical cables (AOCs). The combination of features gives ACCs a peak mix of bandwidth, power, and cost for server-to-server or server-to-switch connections within the same rack.

Marvell announced its first ACC linear equalizers for producing ACC cables last month.

Inside the Cable

ACCs effectively integrate technology originally developed for the optical realm into copper cables. The idea is to use optical technologies to extend bandwidth, distance and performance while taking advantage of copper’s economics and reliability. Where these ACCs differ is in the components added to them and the way they leverage the technological capabilities of a switch or other device to which they are connected.

ACCs include an equalizer that boosts signals received from the opposite end of the connection. As analog devices, ACC equalizers are relatively inexpensive compared to digital alternatives, consume minimal power and add very little latency.